By: Egzon Gashi

On December 3rd, the results for the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) exam were released. As in 2015, the results were alarming - Kosova’s students were near the bottom of the rankings of countries tested and were severely below basic proficiency in all three thematic areas - reading, mathematics, and science. The announcement of the results coincided with a UNESCO conference I was attending in Hammamet, Tunisia on education and inclusion. I represented Kosova and my organization Teach For Kosova at the conference. The results immediately become a topic of conversation at the conference and also back home in Kosova. While they were disappointing for Kosova, they were not surprising.

Between the two tests, in 2015 and 2019, there were subtle changes. The Ministry of Education created a “PISA Commission” which gave more focus to the test and how it was administered; the thought was that because 2015 was the first time Kosova took the exam, implementation affected results. However, this year’s results only reinforced what those in the education sector already knew: Kosova’s education system is not preparing students to fulfill their potential.

How do you reform a broken system? There isn’t a silver bullet, unfortunately. Rather, it takes structural and sometimes difficult change, which must be implemented over time. Over the last 18 months, I’ve immersed myself in Kosova’s education system and learned a great deal from visiting schools and municipalities, speaking to key stakeholders, and developing an understanding of how the system functions.

While the question always seems to be how we can quickly turn things around, the answer is that systemic change takes time, and sustained effort.

Below are a few ways Kosova can begin to create change.

Develop a system of both teacher and school level evaluation

Prior to intervening in any system, it is essential to understand where the issues lie. Unfortunately, Kosova has not effectively developed systems of either teacher or school level evaluation. Reform must be targeted and nuanced according to specific needs of cities, communities, schools, and classrooms.

There are over 23,000 teachers in Kosova’s schools. The teaching profession is seen as a stable job with a relatively good salary. Additionally, teacher evaluation is sporadic and often limited to two or fewer times per year. The highest performing and lowest performing teachers are generally treated the same.

With proper evaluation, schools can identify those teachers are not meeting minimum standards and intervene. If intervention and time does not yield required change, the difficult decision of replacing teachers must be made.

At a school level, directors must be held accountable to their school’s results. Investment and capacity building in data gathering would allow for proper school-level evaluation. After Identifying which schools need the most intervention, municipal level leaders can strategically plan how to divide resources and efforts. Strong school leadership is essential to a high-functioning school.

Recruit and develop the necessary leaders to implement change

If the education system is to be reformed and updated, the right leaders need to be in place to plan for change and to make change happen. Leadership is needed at every level: in classrooms, schools, communities, and in the wider system. And leadership must be collective.

Kosova has a vision for change in education; the 2016-2021 education strategic plan created by the Ministry of Education together with both national and international partners has very modern and forward-thinking plans for reforming education. However, there exists an enormous gap between planning and implementation. The right leaders with an understanding of how to interpret and implement reform will begin to bridge this gap.

De-politicize the education system at a national and municipal level

When discussing education in Kosova, the words “politicized” and “corrupt” are often at the beginning of any conversation. Municipalities hire directors and teachers based on political party affiliation rather than merit. Additionally, change in political leadership leads to change in both personnel and vision-setting at the municipal level. What municipalities need is a clear education vision that is informed by schools, leaders and importantly - the community. A clear vision would not be deterred by change in leadership.

One immediate change that can be made is in the teacher recruitment process. Today, municipal leaders make hiring decisions. However, evidence shows that when school directors are able to hire and manage their own staff, they can create a more effective school environment. Giving this discretion to school directors also makes it significantly easier to hold directors accountable to results.

A second more systemic change that can be made would be the introduction of community-level school boards. Rather than be political appointees, these school boards could be representatives of the community who have worked in education and understand both the strengths and needs of the school system. Oversight from school boards can hold municipalities accountable for hiring decisions and can provide strategic advice on reform and its implementation.

Overhaul teaching methods

A teacher’s role in the classroom should not be to teach at children, it should be to facilitate learning. In too many of Kosova’s classrooms, memorization remains the main way students learn. Not only do teachers expect students to repeat what they said during formal and informal evaluation - sometimes they expect the repetition to be word for word. This teaching method actively suppresses critical thinking, the very aspect of knowledge that the PISA exam attempts to evaluate.

Most of Kosova’s schools also have a teacher-centric classroom. Children are seated in rows with the teacher front and center while students are hardly ever given a voice or chance to lead. Effective classrooms facilitate conversation among students, allow for debate and disagreement, and work to slowly and subtly transfer the process of “teaching” to the students themselves.

In addition to this, Kosova’s classrooms prioritize theoretical over practical learning, in nearly every subject. Students learn best when they are able to both relate and apply their knowledge in practice. Classroom activities, projects, and real-world application of learnings are a few ways this can be done.

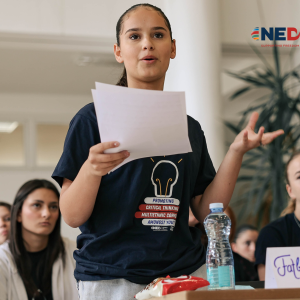

Empower and give students a voice for change

The tragedy of education is that its most important stakeholder - the children - is often not included in any decision-making. Students are eager for leadership opportunities and to be able to apply themselves. School-based governments, community-level projects, and teachers who actively listen to or engage students in conversation, are effective ways of empowering students.

When visiting Kosova’s schools, I often asked students the question of what they hoped to do when they got older. Nearly half, if not more, responded that they wanted to eventually both study and live abroad. Kosova’s youth is its most valuable resource; unless the country figures out a way to develop an education system which allows them to fulfill their potential, it will lose them.